Jack Stuppin: Articles

by Donald Kuspit

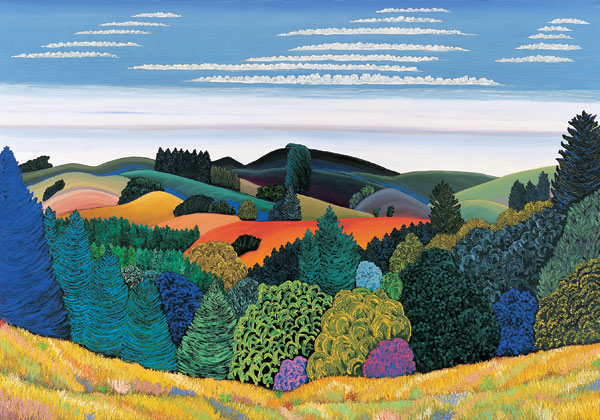

Rich with color, in a seemingly infinite variety, tone after tone at odds yet oddly complementary—thus earth brown and lush green, along with passages of orange and yellow, all luminous, intensely given, nature’s presence insistent through living color—Jack Stuppin’s painting is a marvel of hypnotic hues, swirling together in kaleidoscopic intimacy, not to say patchwork complexity. The painting is meant “to honor the Hudson River School painters,” as Stuppin says, but Stuppin’s work is radically different from their works, for the paintings of Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church, Asher Brown Durand, and Thomas Moran, among those of many others, are representational rather than abstract, as Stuppin’s is. They describe, with insistent precision, a carefully observed scene, whereas Stuppin’s painting evokes—indeed, seems to generate--it through pure, raw color and expressive, dramatic shape. Perhaps despite himself, Stuppin is a modernist, as the all-over flatness of his painting and the polyphonic arrangement of his rich colors, to allude to Clement Greenberg’s idea of classical modernist painting, strongly suggests. Stuppin’s painting, with its modernized, streamlined, even schematized nature—the colors signify it, rather than convey its material substance, its primitive density, even as they convey its primordial presence, its vivid givenness--belongs to the grand tradition of musical painting, initiated by Kandinsky. In sharp contrast, the more traditional—dare one say conventional?--paintings of the 19th century Hudson River artists are what Greenberg called literary or narrative paintings, more pointedly journalistic reporting in pictorial disguise, that is, for them nature was a storybook. They are keen observers of nature in all its detail rather than play its colors as though they are keys on a piano, each color-sound resonant with autonomous feeling, as Kandinsky said. Indeed, Stuppin’s painting is much more alive with feeling—all but uncontainable, for the colors reach beyond the frame, deny its limits—than the more focused paintings of the traditional Hudson School paintings.

Stuppin is a romantic abstractionist, as the inner—deeply personal, existential--meaning of his painting, implicit in its title and his remarks about it, and above all its structure, suggests. “Growing up in NY I always enjoyed the Fall colors I raked lots of leaves,” Stuppin writes. Raking colorful autumnal leaves once again in his painting, Stuppin returns to that happy, yet oddly sad, moment in his youth. For the leaves have fallen to the earth, become so much dead matter, paradoxically alive with color. The painting resonates with memory—the leaves, like Proust’s madeleines, are a remembrance of things past, a nostalgic reside of lost time The elderly painter Stuppin in communion with nature, the leaves of its trees made colorful by death—flaming like meteors before they disappear into oblivion—is once again the solitary youth raking leaves in Yonkers, his hometown on the Hudson River. Reliving the past, re-experiencing a moment in his history, he creates a painting of memorable beauty, gorgeous integrity, aesthetic eloquence. More pointedly, the fallen dead leaves suggest that that the eighty-five year old Stuppin, physically compromised yet emotionally uncompromising, is preparing for the fall into death. The colorful leaves of Fall cannot help reminding him of it—the swirling leaves perform a dance of death--and of his colorful life. After Fall there is Winter, when the brazen leaves will turn to dead dust. Stuppin’s painting is at once a sort of memento mori and the last hurrah of a life well-lived.

But all is not lost—death is not triumphant. In the center of the painting the apex of a large blue triangle, stuck between two low-lying pincer-like growths, each black with death—a sort of Scylla and Charybdis—but vigorously standing and rising above them, points to the full pink moon suspended in the right corner of the sky, as blue as the mountain-like triangle. The phallic-like triangle and the sky are heavenly blue, in abrupt contrast to the heavy earthbound colors. Ribbon-like white clouds accompany the pink moon, confirming its femininity. For the moon is an ancient symbol of the goddess Diana, and pink is a feminine color, suggesting that the painting is a homage to Stuppin’s wife Diana, the goddess caring for him, with extraordinary kindness and concern, as he has said to me again and again. He worships her, and his painting is a prayer to her.

by Donald Kuspit

Professor of Art History and Philosophy

University of New York at Stoney Brook

Ever since Thomas Cole wrote that "all nature here is new to art," American landscape painters have been pursuing landscape that seems too new and fresh to be mistaken as art. Again and again they have sought out "primeval forests, virgin lakes and waterfalls" - nature unspoiled by eyes eager to turn it into art, nature that is not "hackneyed and worn by the daily pencils of hundreds" but as astonishing as the day God made it. (1) It is a nature conducive to wonder not analysis, a nature that seems to contain our own lost innocence rather than a nature ripe for exploitation.

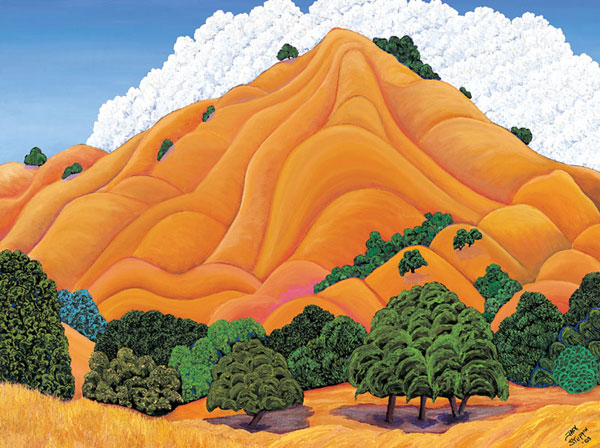

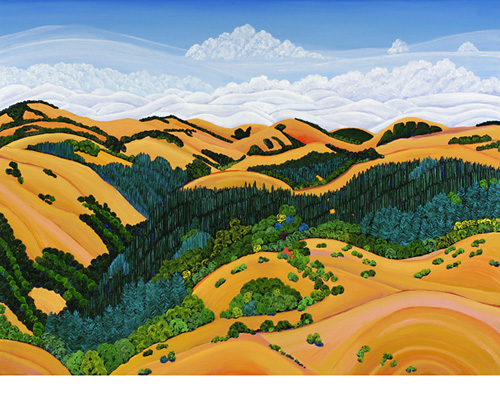

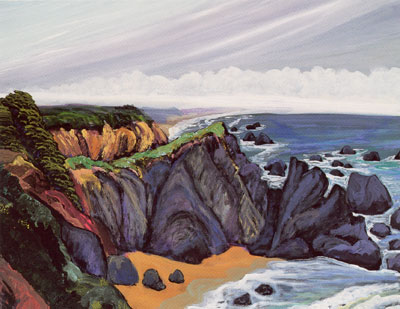

Jack Stuppin has found such nature right in his California backyard. It is nature that has come a long way from Cole's transcendentalized terrain, which set the model for the Hudson River landscapes and luminist vision of Asher Durand and John Kensett. In Stuppin's compact pictures, the American landscape is no longer a demonstration of Emerson's "spirit in the fact" of nature, but rather of the harsh facts themselves, in all their pristine indifference to human existence. Where spirit once spread over the vast panorama of America's unspoiled nature like a benign morning mist, making every detail of plant and mineral and sky and cloud glow with sublime intensity, in Stuppin's pictures the mist has been burned away by a ruthlessly bright sun, leaving behind the raw facts of nature, uncontaminated by either divine or human presence. And nature itself has shrunk, crowded out by invasive society, invisible yet implicit in Stuppin's pictures. Hence their compactness - their air of hermetic self-containment; they are in effect miniature panoramas of nature in its last isolated strongholds. Stuppin's nature is no longer at the heart of America, the way Cole's New England nature was, but at the edge of America. At the limit of the land, Americans can once again deceive ourselves into believing that nature is as vast and limitless as the ocean Stuppin paints again and again. Stuppin has given us a nature whose harshness and inhospitableness defend it against human predation, and also against mystification, that subtler, more wishful way of consuming nature.(2)

Stuppin's nature does not lend itself to projection - to spiritual fantasies, to the pantheistic illusion of indwelling divinity. It is too hard - too forcefully real - to take comfort in: it lacks the soft, atmospheric light of the Hudson Valley, into which the Luminists read the dregs of romantic nature worship. Moreover, Stuppin's nature, however dynamic its appearance, is more dead than alive. Vegetation is sparse, shortlived, and clings for dear life to sere - sun-seared - hills, as Wheeler Ranch, 1989, Fog Coastal Mountains, 1996 and Black Mountain from Cindy's, Marin County, 1994 make clear. In fact, almost nothing is alive in Stuppin's magnificent Farallon Islands paintings of 1995. They are all bleak stone, immense ocean, relentless waves, changing sky, and infinite horizon, as Window Rock, Chocolate Ship, Main Top, Main Top from Lighthouse Hill, and Indian Head make clear. Even Stuppin's luminous paintings of blossoming trees - for example, Almond Trees and Graton Apples, 1997 - are toughminded, as their incisive clarity indicates. For all the lushness of the scene - the dark earth, sometimes streaked with red, the pink and white blossoms, briskly twinkling like stars - it remains understated, even laconic, a brevity of description that gives it an epigrammatic intensity. Stuppin's nature, for all its forthrightness, is not the transcendental paradise of the past, but a very real, down to earth place, too elemental to lend itself to the human wish for leisure time renewal. Stuppin's nature does not tolerate fools.

The problematic that Mark van Proyen finds in Stuppin's Farallon Islands paintings applies to all of Stuppin's works. "The islands," van Proyen writes, "are a federally protected marine sanctuary, inhabited by an astounding biodiversity of sea birds and mammals; a place that is literally teeming with densely packed life. The question, then, is how does one reconcile the culturally transmitted fantasy of the foreboding Farallones with its ecosystemic reality; how do we go about 'seeing' the islands as a place of meaningful psychic habitation?"(3) That is, how did they - and the Northern California terrain - become emotionally meaningful for Stuppin, and what do they tell us about his psyche? At least since Claude Lorraine and Poussin nature has been a kind of screen on which feeling is projected - openly by the romantic landscape painters, and perhaps climactically in the idealizing images of the Luminists. I want to suggest that Stuppin's nature, for all the bright sun that shines on it, is not only far from ideal, nor even ordinarily real, but rather filled with forebodings and signs of fate. The geology in Farallon Islands paintings is a concrete manifestion of it, but so is the seasonal blossoming of fruit and nut trees, for the springtime of life is part of the larger cycle of nature - the repetitive cycle of fate, which ultimately matters more than any of its temporal aspects.

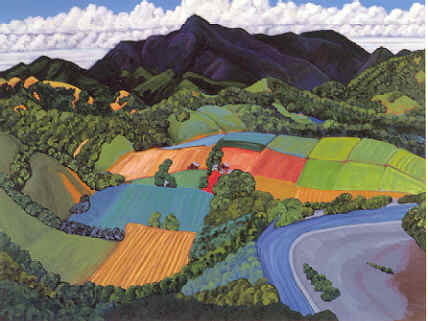

The sea in Stuppin's Surf, Bodega Head, 1996 may be green, as though teeming with life, but the green seems too uncanny to be entirely natural - certainly in comparison with the green of the foreground vegetation - and the waves are as relentlessly repetitive as fate. Indeed, fate shows itself, as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche and Freud thought, and also the ancients, in and through eternal recurrence, indicating that life is bound by certain limits, which are inescapable - fated. Again and again we see this idea of eternal recurrence in Stuppin's paintings, embodied in either waves or rocks - both, in Highway #1, Summer Fog, Rocks, 1996. For me, it is the seemingly infinite repetition of the buds that counts in Stuppin's blossoming trees of life - Apple Blossoms, Coffee Lane, Sonoma Country, 1995 and Almond Trees, University Farm, 1997 are further superb examples - more than the fact of their blossoming and aliveness. In Stuppin's Digger Bend, Russian River, Sonoma County, 1992 the colorful patterning of the farm plots reflects the pattern of fate. Fate ironically overlooks its own appearance in the form of the majestic, dark mountain in the background. Its bleakness - lack of habitation - signals the death that is at the end of the road of the life that will be nourished by the yield of the farm: the death that brings with it recognition of fate - not salvation in supernatural life. The way the geometrical farm precariously clings to the uneven, unstable terrain - the California coastal area, with its hidden faults, is earthquake prone - is another indication of the subliminal presence of fate.

The California coastal area is one of the last places where one can experience fate in America. Western nature in general seems more fated than the rural New England nature visible in 19th century American landscape paintings. For all its unspoiled look, nature seems rather domestic, as the human encroachments conspicuous in much of it suggest. It is not simply the factuality of Stuppin's pictures that counts, but the starkness with which he renders the facts - the "primitive" character of his rendering, as it has been called by John Fitz Gibbon.(4) Stuppin paints the Farallon Islands for the primordial starkness of their nature, indicative of the indifference and relentlessness of destiny, not simply because they are a unique kind of local color. (I think the stark whiteness of the waves, clouds, and blossoms in his paintings signals the indifference of fate, however ironically, all the more so because of its luminosity. The whiteness - absence of color - caps nature with its own transience, a reminder that fate is superior to it.)

Nature is an avenue into - a direct manifestation of - fate in Stuppin's paintings, rather than an empirical or spiritual end in itself, however precisely it is described and however emotionally resonant its complex play of sun and shadow may be. In short, Stuppin does not worship nature, or the God in nature, as the 19th century American landscape painters did, nor does he anxiously idealize it into a recreative alternative to society. Nor is it an ironical holdout against the impending environmental holocaust, already in process. Rather, Stuppin respects nature's sheer givenness, which for him is not so much a symbol of fate, but fate in unqualified action.

NOTES

- (1) Quoted in Barbara Novak, American Painting of the Nineteenth Century (New York and Washington: Praeger, 1969), p. 61

- (2) On a cross country trip in 1992, Stuppin sought out further sites of primordial nature, such as Niagara Falls and the Badlands of the Dakotas, but Northern California remains his preferred site. Significantly, his non-California pictures are even more compact and intimate than those of California, suggesting how harder it is to find authentic, untouched nature elsewhere in America. All one has to do is compare Frederic Edwin Church's painting of Niagara Falls (1857) with Stuppin's to see how much nature has diminished - how much less awesome it has become--in the course of American history.

- Today there is much less primal nature in the United States than there once was, and what there is has been deliberately preserved as a privileged site - which is the irony of the Farallon Islands. The wonder, awe, sense of spiritual promise materially fulfilled, and sense of being in the presence of something altogether unique and radical, that accompanied the first discovery and experience of the American landscape is no longer possible today. Nonetheless, it is still possible to have a feeling for the primal, as Stuppin's landscape paintings show.

- (3) Mark van Proyen, "Offshore' at the California Academy of Sciences," Artweek, 28/11 (November 1997):20

- (4) John Fitz Gibbon, "A Barmecide Feast," Barmecide Feast: Landscapes and Figures by Jack Stuppin (Bolinas: Pegasus Press, 1996; exhibition catalogue), p. 2

by Mark Van Proyen

Professor of Art History, San Francisco Art Institute

Contributing Editor, Art Week magazine

An Essay on Painting, Shaftsbury (1713)

During the final decade of the 20th century, it was fashionable to view the entire idiom of landscape painting in terms of its representation of civilization's "imperial" power over the land, casting it as the means of conveying a kind of pseudo-historical myth and idealized proof of the rightness of civilization's dominion over nature. Witness W.J.T. Mitchell's claim that "landscape might be seen more profitably as something like the dreamwork of imperialism," ... if Kenneth Clark is right to say that "landscape painting was the chief artistic creation of the nineteenth century," we need at least explore the relation of this cultural fact to the other chief creation of the nineteenth century - the system of global domination known as European imperialism.(1) Of course, statements like this can also be taken as the artifacts of a another kind of dreamwork; that being the casting of academia's relationship to late 20th century history as a wishful attempt to re-determine the corporately controlled present via an exegetical framing of the not-so-mythical past. As such, it can be said to evade the important - indeed, the crucial issue of our time, that being the one which asks how we might most fully inhabit our own moment in our own time, disengaged from the pull of superordinating presuppositions and in un ambivalent possession of a psychically self-sufficient moment of temporary isolation from an insane world overdetermined by policy mandates and the rote groupthinks which are bred from an endless and irresolvable contest of cultural politics.

Jack Stuppin's landscape paintings are remarkable for the directness and clarity with which they address themselves to this issue of spontaneous psychic inhabitation, and because of this, they take us to places where the angels of anxious sanctimony fear to tread. Not that they do anything wrong; on the contrary, theirs is the most innocent and uncontroversial of artistic tasks, that being the capture and alignment of the momentous confluence of time, place and atmosphere which memorably comprises the irrepressible psychic scenery which cultural politics always seeks to deny and drown out. And yet, it cannot and will not be denied, because all of the abstract information in the world cannot even begin to compete with the tangibility of actual experience in terms of real impact on human memory, however precise, coherent and well-ordered such information might pretend to be. In the end, memory will of necessity trust experience over hearsay, and observable pattern over even the most logically consistent of speculative possibilities. To state the same thing in plainer words, we can say that the meanings that memory makes always places experiential moments in its forefront, emphasizing them as vivid markers for expedient recovery as well sustaining them as keynotes and catalysts for further investigations. This stems from the fact that we are all fated to be haunted by images even as the will to self-protection makes us skeptically suspicious of sermons and diatribes, and images are of necessity always located in some kind of place.

Stuppin's landscapes address themselves to exactly this notion of perpetually-present memory in that they always seek to collapse and cement the difference between time-present and time-past, re-making them as one-and-the-same as an all-at-onceness which reminds us of the popular truism stating that time is God's way of keeping everything from happening all at once. Open-minded yet decisively assured, Stuppin's paintings lift us to the Olympian vantage of geological time where everything pretty much does happen all at once, again-and-again, and they are remarkable for the different paths that they take to carry us to the threshold of that vantage, giving us both its complex topographic texture and well as its eternal panoply of elements - the difference-within-wholeness that is the very essence of the long tradition of landscape painting as it continues to exist in Europe, Asia and North America. If we ascertain within these works a once-upon-a-time magic, then we are also reminded of the delightfully inescapable fact that said time and place is our own here-and-now. Stuppin's paintings remind us that it is the land itself that is the place which contains all possible places (as both Ur-source and final teleological destination), so they make a perfect, almost heroic sense in that they portray, and thus contain the thing that is destiny tells us will finally contain everything else.

Laboring within the long shadow of both Kantian and Hegelian Idealism, the German art historian Max J. Friedlander stated what has since become a truism for the modern reception and practice of landscape painting: land is the thing-in-itself, landscape the phenomenon.(2) Even though Stuppin's paintings always take a specific geographical location as their point of departure, their "landscape-ness" should primarily be understood as a model of the mind in so far as they reveal themselves to be idealized imaginings of an a temporal perpetuity. In this, they are demonstrations of the rigors and vigors of an everymind which seeks to wrap itself around the complexities of any given situation that strikes its fancy. To be a bit more precise, we should probably say that Stuppin's ebullient landscapes are models of being which the mind has chosen to inhabit with a set of specific temperamental priorities and consistent attitudes: obstreperous, playful and perhaps a little impatient to reach a pictorial conclusion about a subject that can never be concluded. Perhaps this recognition casts the repeated effort to reach such a conclusion as a kind of repetition-compulsion giving way to momentary Phyric victories which provide a quick and essential glimpse of that larger-than-lifeness which can only regard the so-called drama of our own existence as a short and rather brutish epiphenomena. But it also gets us closer to how the land can become a site for the projection of a wealth of subliminal meanings which reflect the whole array of styles-of-experiencing which we call life.

Other writers have alluded to some of these meaning in vivid and provocative terms: for John Fitz Gibbon,(3) Stuppin's "primitive" landscapes are condensed cornucopias of nature's delectable abundance ... paeans to the benevolent vision of plenitude symbolized by the many-breasted goddess Diana of Ephasus. Sounding an almost diametrically opposed note, Donald Kuspit has pointed to how they reveal the fact that "the American landscape is no longer a demonstration of Emerson's spirit in the fact of nature, but rather of the harsh facts themselves, in all their pristine indifference to human existence. Where spirit once spread over the vast panorama of America's unspoiled nature like a benign morning mist, making every detail of plant and mineral and sky and cloud glow with sublime intensity, in Stuppin's pictures the mist has been burned away by a ruthlessly bright sun, leaving behind the raw facts of nature uncontaminated by either divine or human presence."(4) Even though we might think that these statements are at odds with each other, we should take pause to consider the fact that they take different individual works, or at least different clusters of Stuppin's typical subject matter as their respective points of literary departure. Clearly, Fitz Gibbon is thinking of the perfervid spring and summer moods of pastoral works such as Mesa on Ghost Ranch (1999), or Hill at Wharton Hollow (1998), where rude bursts of sumptuous foliage impinge upon successive ranges of undulate hills and pillowy valleys which are typically regarded from an elevated panoramic vista. Kuspit's assertion of the immutable remorselessness of nature is revealed in the upsurging rocks and barren crags pictured in paintings such as Main Top from Lighthouse Hill, Farallon Islands (1995), or perhaps in the sun-scorched hills pictured in Fog and Coastal Mountains, Sonoma County (1996), Both of these paintings take the dramatic confrontation of sun, sea, and land all pounding hard against one another as their subjects, and they remind us of the fact that Herman Mellville's grim vision of nature as a place where all creation "be tooth'n and fang'n one another" is just as characteristic of the American spirit as are the meditative idylls of transcendental nature mystics such as Thoreau and Emerson.

Other epiphanies are revealed for our viewing pleasure in Stuppin's paintings. Blossoming fruit trees of the type pictured in Three Plums (1997) and Almond Trees, University Farm (1997), are painted in a way that typically emphasizes their brilliantly efflorescent chromatics, all-the-while laboring to suppress excessive detail in a way that makes them seem more like the idealized remembrances of a particular moment rather than the specific pictorial recollection of a given location. These works literally pop into our visual word, seeming almost improbable in their convulsive bushiness. At first glance, their picture-spaces appear to be flattened in the distilled, economic manner of those painters which we associate with Modernist movements such as Fauvism, Die Brucke Expressionism or the Nabis. This flatness, combined with these work's electric colors (which never become sour or overripe) quickens our eye, making us remember what it was like to be particularly alive to a particular moment in a particular place that is in itself particularly alive. This is accomplished by the way that the paintings prompt us to achieve high speed in our apprehension of the interrelation of complex pictorial incidents as they coalesce into the general view. It also beseeches us to savor the exhilarating chromatics of that view, forcibly re-acquainting us with the omnipresent epiphanies that are always lurking amid moments of everyday perception.

It is at this point that we realize that there are specific particulars inhabiting these scenes, uniquely memorable ones at that. These are revealed in the form of seemingly improbable details that seem somewhat insignificant in themselves, but in fact are the telltale giveaways to the actuality of the scenes portrayed by these works. To those who are familiar with the Napa, Sonoma and Marin County backroads that Stuppin most often uses as his en plein air studio, the shock of recognizing these details creates a kind of credibility of remembrance in that we can compare our memory of these locations with Stuppin's fanciful rendition of it - thereby allowing entry into *seeing* that location in the specific frame of mind and perhaps even the specific imaginary moment in which the artist initially viewed it. For those who are not blessed with such geographic familiarity, those details offer themselves up as contributing textures which again remind us that landscape is always more than a mere geological parable. Rather, it is the disclosure of a cyclic narrative of becomings and diminishments which locate both as the polar points of some perpetual cosmic respiration, to which we are all connected regardless of whether we recognize it or not. But the momentousness of this recognition is enhanced if we are also able to recognize the precise moment from which it stems.

It is in this use of specific incident to anchor and apply texture to the general scene that we see the true character of Stuppin's art. His paintings neither seize the topical nor insist on the authority of the general view as an exclusive procrustean province, opting instead to unite these disparate polarities into a flexible, almost paradoxical continuum. They are "down to earth" even as they are never mired in it, always choosing to be unabashed in partaking of whatever pleasure are offered by time and place without making any kind of a moral issue over the powers which shape those moments, which at their essence are always indifferent to the anxieties and conceits of such powers. Once that indifference is noted, the land comes out from behind its passively picturesque shadow and shows itself to be a frisky Poseidon frolicking with the shy creatures of his endlessly fascinating dominion, revealing its supple musculature while remaining confidant and relaxed, unpossessed by any crippling tension bred of an apraxic self-consciousness.

Throughout the past two centuries, many painters have returned to working in and with the landscape to partake of the rejuvenation and spontaneity that goes hand-in-hand with a momentary liberation from the enforced miserablism that is bred from seemingly endless and ever-more arduous quotidian routine. Some, like Gaugain, have never looked back, and in fact they made it their business to stay as close to the land for as long as possible, knowing that it would take much longer than an ordinary lifetime to unlock its knot of secrets and exhaust its many pictorial possibilities. I suspect that Stuppin can rightfully count himself among those artists who have taken the land's temptation to the point of almost going native with it. He certainly continues to find new vistas to inhabit and respond to, and the work seems to grow ever-closer to revealing what the Taoists call "the living breath of land and rock." In this, Stuppin's work can be said to respond to same vitalist impulse that motivated and inspired the scholar-painters of the Sung dynasty almost a millennium ago:

"Landscapes are large things. He who contemplates them should be at some distance; only so is it possible for him to behold in one view all shapes and atmospheric effects of mountains and streams. It has been truly said, that among the landscapes, there are those fit to walk through, those fit to contemplate, those fit to ramble in or to live in. All pictures may reach these standards and enter the category of the wonderful; but those fit to walk through or to contemplate are not equal to those fit to ramble in or live in ... the wise man's yearnings for woods and streams is aroused by the existence of such beautiful places ...This may be called not losing the fundamental idea." (5)It is in the way that Stuppin's paintings embrace "the fundamental idea" of psychic inhabitation that we see their importance and value. These are works that prompt us to that inhabitation, and in so doing, "do something for us," that is, they facilitate our understanding of connectedness to the living onement that is both time and place. They prompt us to stop pretending to believe in the reality of the speculative and the intangible by reminding us of the tangible albeit unfathomable mysteries which lurk in that which is immediately at hand.

- (1) W.J.T Mitchell, Imperial Landscape, in W.J.T. Mitchell (ed.) Landscape and Power, University of Chicago Press, 1994. p. 10.

- (2) Quoted in Jed Perl, Earth, (1997) in Eyewitness: Report from an Artworld in Crisis, New York, Basic Books, 2000. p. 171.

- (3) John Fitz Gibbon, A Barmecide Feast, Barmecide Feast: Landscapes and Figures by Jack Stuppin (exhibition catalog) Fairfax, CA. Bradford Gallery/Pegasus Press, 1996; pp.2-3.

- (4) Donald Kuspit, At the Edge of the World, (exhibition catalog), New York, Nieman Gallery, Columbia University, 1998. pp. 4-5

- (5) Kuo Ssu, The Great Message of Forests and Streams, (c. 1050 C.E.), in The Chinese on the Art of Painting, edited with an introduction by Osvald Siren, New York, Schocken Books, 1963. pp. 43-44.

by Miriam Roberts

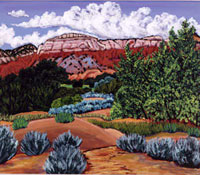

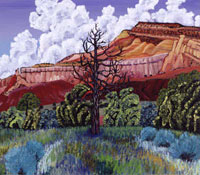

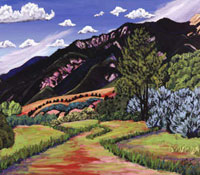

Jack Stuppin has done most of his work among the lush hills, orchards, rivers, and coastline of Northern California. In recent years, however, he has occasionally traveled 1000 miles southeast to the high desert of Northern New Mexico.

In his journey, Stuppin is following a well-worn path. Artists began coming to Santa Fe and Taos in the late nineteenth century in a steady stream that continues unabated into the twenty-first. Modernists like Marsden Hartley, John Sloan, John Marin, Stuart Davis, Maynard Dixon, and Andrew Dasburg have all made the trek - some passing through and others, like Georgia O'Keeffe, staying long enough to become known, at least locally, as local artists. Many contemporary artists continue to paint the New Mexico landscape, but Stuppin is one of the few remaining true en plein air painters - practicing the art of painting outdoors, not from photographs in the studio.

Like every good artist, Stuppin has absorbed - consciously or unconsciously - the history and tradition of his medium. He is passionate in proclaiming his belief that the genre of landscape painting remains meaningful to the viewer and to society. Donald Kuspit notes that Stuppin's paintings relate to the Romantic tradition in American landscape painting, but divested of references to divine or human presence.

More recent precedents can be found in European modernism. Stuppin learned the expressive potential of the landscape from the paintings of van Gogh and Matisse. The West Coast roots of his art are clear in Stuppin's insistence on merging representation with abstract gestural and expressive elements. One thinks of artists from Joan Brown and Roy De Forest to Wayne Thiebauld.

Stuppin paints methodically. He typically sets up in the morning and works into the afternoon, painting from top to bottom, as if slowly pulling down an inverted window shade to reveal the landscape he sees. The places his paintings depict, in straightforward compositions of form and color, look primal, almost untouched by humans. His New Mexico landscapes are devoid of scars from overgrazing and other human practices.

Instead, Stuppin's paintings are full of wonder and amazement at pristine nature, painted by a man completely at home in this world. Stuppin's paintings produce a serotonin rush of pleasure. In part this comes from the kind of naiveté or innocence they embody, and in part it comes from their visual richness. But there is more at work on these surfaces. Stuppin employs a series of compositional strategies - rhythmic patterns and careful juxtapositions of color - calculated to capture and reveal the essential unifying principles of the natural world. The paintings provide us with a sense of the sacredness inherent in each moment and each place, to which we are invited, along with the artist, to feel, to contemplate, and to revere.

Even to a person familiar with his paintings of the rocky California coastline and orchard-covered hills of Sonoma County, Stuppin's Northern New Mexico landscapes can be startling. Hardly anyone will fail to recognize the rock formations, the pinons, the junipers, and the sage - either because they have seen them themselves or because they have been exposed to the paintings and photographs of Georgia O'Keeffe and Ansel Adams - but the conventions of representing the place are decidedly missing. Gone are the vast expanses of timeless space, replaced by tightly compressed visual fields pulsating with energy. Gone are the sun-bleached hues, replaced by colors of blinding intensity. Gone, even, is the arid beauty of the high desert, replaced in Stuppin's hands by a landscape that is positively lush and verdant.

Stuppin's paintings can be seen as the artist sees them himself - as end products of the process of standing in nature and transforming perceptual experience into art. They can be seen, as Kuspit asserts, as philosophical meditations on time and fate. They can even be seen as the artist's mischievous art-critic friend John Fitz Gibbon describes them - as delectable conflations of two genres, still life and landscape. It is a humorous notion: where Stuppin paints rocks and trees, Fitz Gibbon finds carrots and broccoli spears. But, whether these paintings record the vision of an intrepid lover of the world or the cosmological musing of a hungry man, what begins as a visual feast for the viewer ends up as an immensely soul-satisfying experience.

- Sage at Ghost Ranch

1999, Acrylic on Canvas, 24 x 30

- Chimney Rock, Ghost Ranch,

1999, Acrylic on Canvas, 24 x 31

- Sacred Taos Mountain,

1999, Acrylic on Canvas, 24 x 31

by Peter Selz

Professor Emeritus of Art History

University of California at Berkeley

The area of Sonoma County near Bodega Bay and the sea is an arid land of rolling blonde hills spotted by clumps of dark green trees. Often the morning banks of fog blur the landscape, and then near midday the trees, the streams, the ocean, and the outcroppings of rocks appear with lucid accuracy gleaming once again in the California sun. This is a land in which the live oak, redwoods and cypress are still plentiful. Apple orchards and vineyards abound below the hills, golden with dry grass for much of the year. It is here, near the town of Sebastopol that the New York born Jack Stuppin found his sense of place and the inspiration to paint it. Twenty-five years ago the Sonoma Hills were delineated by the Christos' Running Fence which marked the hills, fields and Bodega Bay. But instead of intersecting the land, Jack Stuppin numbers among the artists who have chosen to paint the landscape en plein air once again.

John Constable, who was in fact one of the first plein air painters, wrote: "The landscape painter must walk the fields with a humble mind. No arrogant man was ever permitted to see nature in all her beauty." He painted the English countryside around Salisbury with amazing freshness and audacity, creating sketches in which every brush stroke conveys his understanding of nature and the revealing/concealing quality of its light. But in the early 19th Century the time had not yet come for the public to appreciate this kind of "unfinished" painting and Constable kept those masterpieces to himself, exhibiting only the finished oils which seem labored and prosaic by comparison. It was left to the Impressionists to astonish the public with their paintings in which forms were dissolved and dematerialized by light to depict the impression of optical manifestation. With the ensuing trends toward art which was no longer subject to the restraints of appearance, modernist art marginalized naturalist painting en plein air to something like an underground existence practiced largely by Sunday painters.

Jack Stuppin, no Sunday painter he, has been exhibiting his work since he was a painting student of Sam Tchakalian, Bill Allan and Jay de Feo at the San Francisco Art Institute in the late 1960's. For a good many years now, he has gone out each day from his beautifully located house in search of the right landscape. He drives on the country back roads, stops when he sees a captivating view, takes out his easel, canvas and acrylic paints, begins to picture what he sees and then, almost intuitively, organizes it into vibrant paintings. These are the works of an artist for whom a frequently painted view of a mountain, an apple tree, a field of flowers, scattered clouds or a winding creek is always a new experience. The scenery does look different every day and exciting things happen on the canvas each time Stuppin applies his brushes and vibrant colors.

The Estero Americano, a narrow stream as it meanders through Valley Ford towards the ocean, served as a subject for several of the artist's recent paintings. Painted at different times of day and season, the pictures display colors for the long hillside that vary from bright orange to tawny sand. In some landscapes there is a streaky sky, in others there are puffy clouds, changing the mood of the paintings. From the marshlands on the north side of San Francisco Bay, Stuppin made the fine painting, Bayland (2001), done on linen, as are many of his recent small acrylics. It is a composition of horizontal and curved honey-colored dikes set in blue water. The curves of the levee and the white ripples on the inlet at the bottom of the painting are echoed by the sweeping cloud formation in the sky. The artist insists that the little seascape and the clouds were painted as they actually appeared. This is also true of the flowering apple tree Upp Road Apples (2001), in which profuse blossoms, thousands of small diamonds, spread against the green grass with a purple Mt. St. Helena looming in the background. Writing about Stuppin's Apple Blossoms, the astute critic John Fitz Gibbon, tells us that we learn about the Earthly Paradise when we look at these paintings.

Mustard, Coffee Lane (2001) is one of the subjects of delectation the artist finds on his neighbor's property. He paints a field of flowering yellow mustard with large, strong Douglas firs on either side of the meadow opening up to distant hills. A light blue sky is animated by a flock of sharp diagonal clouds and a large billowy cloud over a tall tree. There is a sense of empathy with the land and sky. The joy and delight expressed in these pictures convey an authentic experience in seeing and painting.

It is worth noting that in spite of the vast difference in their paintings, Jack Stuppin would agree with Hans Hofmann, that "plastic creation asks for feeling into the essentiality of nature as well as the essentiality of the medium of expression." In his early years, before he turned to expressing himself by working directly from nature, Stuppin did paint in an abstract mode. In some of his recent paintings he has adopted a three-way process: he first paints the landscape en plein air in acrylic, then he makes a digital photograph of the work which serves him for a larger painting, done in oil in the studio. Even Claude Monet, the plein air painter par excellence, completed his great waterlily suite in the studio before hanging it in the l' Orangerie.

Jack's final oil versions are fairly large. Russian River at Willow Creek (2001), for example, measures 48" x 60", and unlike most of his paintings was done on canvas that is mounted on a wood panel. Transformed from the original plein air acrylic, the second version maintains the almost innocent freshness of the first state and maintains the vibrancy of color, now highlighted by the gloss of the oil surface. In all his paintings Stuppin maintains the bright light of the midday sun, even if they were painted in the early morning or toward dusk. We see a medley of colors in Stuppin's work. In this painting ultramarine trees rise above a gently curving apple green hill that is outlined by a narrow orange band. A claret colored group of rocks juts out from the banks of the light blue Russian River. Green, we know exists in the greatest variety of shades in nature and in this painting innumerable kinds of green pigments have been used. An even greater assortment of colors is found in a recent oil, St. Helena, Digger Bend, Fog (2001), which appears like a crazy quilt of brightly colored pieces. The landscape is surmounted by a purple Mt. St. Helena, which is a source of a great many of Stuppin's landscapes. We are reminded of Cézanne, who painted Mont Ste. Victoire sixty times over a period of 28 years. However, Cézanne analyzed the mountain into abstract components reconstructing it by his brush into a symphony of luminous colors, changing the history of painting. Jack Stuppin has not embarked on so ambitious a project; he is satisfied to reproduce the mountain, as it looks in its wide expanse - sometimes in a cerulean blue, at others in a stark pure purple. In the "Digger Bend" painting a white bank of fog spreads horizontally across the valley below the mountain. Under the fog are the blonde, curving hills, wide groups of trees, tilled fields, and small barns that are painted red, as is a small plot in the center of the canvas. The more we look at these paintings, the more we discover in the variegated landscape. In this painting as well as in St. Helena, Alexander Valley, tawny hills sweep down to cultivated fields, which are tilted upwards, minimizing perspective and reducing space toward the two-dimensional plane. In the "Alexander Valley" picture the composition is anchored on the right hand side by a grand conifer with widespread branches. Painting the scene as it appeared to him while standing at his portable easel, Jack Stuppin intuitively reorganized it into a structured pictorial composition. He once studied the art of flower arrangement in Japan, and in his choices of color as well as in his sense of organic order, this training clearly comes to the fore.

In his 1998 essay on Stuppin's paintings Donald Kuspit makes us aware of the "impending environmental holocaust, already in process" and this artist's "respect for nature's sheer givenness." Jack Stuppin is very much aware of the importance of conserving what is still left of the land. The beautiful forest on his property will eventually be put into a conservation easement. His joyous and vivid paintings in which the land is transformed into resplendent "land-scapes" are not only fine objects but reminders that the land must not be "developed" or destroyed and recall Wallace Stegner's warning in his famous "Wilderness Letter." In 1960 Stegner wrote:

"If we ever let the remaining wilderness be destroyed; if we permit the last virgin forests to be turned into comic books and plastic cigarette cases; if we drive the few remaining members of the wild species into zoos or to extinction; if we pollute the last clear air and dirty the last clean streams and push our paved roads through the last of the silence, so that never again will Americans be free in their own country from the noise, the exhausts, the stinks of human and automotive waste. And so that never again can we have the chance to see ourselves single, separate, vertical and individual in the world, part of the environment of trees and rocks and soil, brother to the other animals, part of the natural world and competent to belong in it. We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring our-selves or our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope."Sensual Landscapes by Peter Frank

Art Historian and Critic

As plein air painters go, Jack Stuppin is something of an anomaly. He paints what he sees and paints as he feels; he paints in the moment and paints for later reconfiguration; he focuses on natural surroundings and he privileges the human gaze - in other words, he manifests all the dynamic contradictions upon which the practice, even the very idea, of plein air painting is grounded. But Stuppin's results are not those of most plein air painters. Rather than capture a fleeting second of atmosphere in the eternal passage of natural time, Stuppin immediately finds a monumentality - albeit a living monumentality - in the terrain and its living skin. The land before us will always be before us, Stuppin's work avers, shaped more or less as it is shaped. The vegetation coating the land will live and die and live and die and live and always change, perhaps drastically, in the process, but there will always be something alive on the face of this earth - providing, of course, that in our heedlessness we don't strip the land bare ourselves. And if we do, the land itself will still be there, stolid and reproving in its new nakedness - a nakedness that, in Stuppin's painting, it hints at even now. (Can we call this our "just deserts"?) Stuppin's art reasserts and celebrates the redoubtability of nature.

But it also reasserts and celebrates the redoubtability of art and of the human spirit. When he began painting en plein air in the late 1980s, Jack Stuppin was far less concerned with (although no less aware of) the history of art and the professional role(s) of the artist than he has become. Even if this did not allow Stuppin a veristic "capture" of time and place, it allowed his painting a less alloyed access to his own sensations, helping to establish a feedback loop between the seen world and the sensed that has impelled his work since. Stuppin's hand could not keep up with the virtuosic plein air tradition, so his eye had to work fast and his heart had to work faster. It is this aerobics of plein air that Stuppin exercises in every painting he makes - whether en plein air itself or back in the studio. And he long since found that the stylized, even abstracted, approach that came out of his brush was, yes, natural to him, adequate in its faithfulness to the appearance of the land, and perfect in its embodiment of his sensations (and by extension ours) to the overall experience of nature.

Although Stuppin's manner smoothes the contours of terrain and vegetation into almost patterned reason, and tames (or at least calms) the burro-like recalcitrance of oil pigment into comparatively genial cooperation, there is still a vivacious spirit he finds within and without, in his hand as in his view. Indeed, his work, increasingly, establishes an uninterrupted circuit between the polarities of his perception, inner sensation and outer observation. These are not landscapes by Jack Stuppin, they are landscapes of Jack Stuppin, "about" the artist no less and no more than about the natural space he inhabits.

In paintings such as Red Ocean Song, for example, or the aptly named Joy, details of the landscape are not just stylized, but transmuted, their colors heightened, as in the vivid crimson hillock that burgeons in the middle of Red Ocean Song, their contours sculpted, as in the roller-coaster slopes that dominate Joy - and, for that matter, in that painting's shrubs, each a Brussels-sprout-like bolus, and its trees, most notably the blue-green fir in the picture's middle, its foliage in a vigorous upsweep that reflects the painting's spirit of elation. Such landscapes are designed not only to provoke emotions, but to embody them. Red Ocean Song is a song of nature, both about nature - sung by Stuppin in paint - and by nature. Joy is not just joyous, it is joy itself - Stuppin's joy, ours, the trees' and bushes'. The poetic trope of attributing human emotions to non-human entities may be a corny concept; but it works for Stuppin, much as it has worked for painters throughout the last hundred-plus years.

Perhaps this flow of response, even of identity, results from Stuppin's devoting more and more time to living amongst the hills and clouds, ocean waves and clumps of bushes that constitute California's North Bay coastal landscape. More likely, the flow results from Stuppin's devotion of more and more time to the rendering of these views - that is, both to looking at the subject and to painting it, with a discipline born of passion and a focus born of awe. The rhythmic counterplays and expansive sweep of a shore painting like Bodega Head, where the knobby foam breaker caps mirror the striated rows of clotted clouds and the brown cliffs spill out like lava from coastal gorse and black rocks, constitute an orchestration of miracles, an evocation that strains credulity the way nature itself does in places like these. Likewise, the tawny ripples that comprise the flank Golden Hill shows us, an exaggeration of the real thing, will seem comic to anyone not familiar with California hills (or with their similar caricature in the landscapes other artists have painted in California since the state's original plein air school was active). But one glimpse of this or a similar hump anywhere west of the Sierras makes a believer of anyone; Golden Hill is still endearingly comical, but it is also entirely believable. Stuppin has painted the beingness of the hill, in a conflation of his consciousness with the hill's essence - a kind of Zen "Sound of Music," improbable, hilarious, moving.

Does Stuppin, then, "disappear" into the hill, into the landscape? By inference, he does so bodily; any trace of human presence, his or other', is absent from his vistas, and in fact the biggest liberties he takes with what he sees is in the erasure of human-made structures (although for the most part he finds views that have none to begin with). But spiritually as well, Stuppin can be said to be disappearing into the landscape. His identification with the Sonoma coast is thorough; his mind and eye are no longer simply situated at it, but have become to a great extent of it. He has effected in himself the exchange of the viewer's ego for the superego of the artist - and the id of the landscape itself.

Note that the ego-surrendering identification here is with the Sonoma coastal landscape, a very specific microclimate where the characteristics of California's semi-arid central valley meet and mix with the qualities of wild, untamed beach fronting on cold, relatively placid but constantly seething waters, all taking place on geologically active (even, in places, once-volcanic) terrain. This, as we see in an alternately verdant and sere picture like Fog, Golden Hill or in the bizarre - but in this region frequent - cloud and vegetation patterns of Cloud Parade, is a region of suddenness, of hardy brown grasses giving an almost animal-like hide to the muscular folds of big hills and small mountains while arrays of evergreens and gnarled bushes creep up their sides and clumps of flowers burst forth seasonally in gaudy displays of color (not to mention scent). The whole thing glimmers underneath a brilliant blue sky; the nearby sea may temper this sky with a soupcon of moisture, but it also reflects sunlight back up into the heavens. The resulting intensity of light diminishes only when the fog begins its daily march inland: what had sat like a thrown-off comforter on the other side of the rocks and dunes now comes in, to modify Sandburg's image, on big cat's feet, stalking and ultimately blanketing the landscape in a cool gray, more mysterious than dour. Stuppin has painted other places, but each time he has he has either to adjust his regard - to operate first from ego as well as observation - or to "cheat," and treat the new region as a variation on the Sonoma coast. These gambits have proved workable, even visually satisfying, but they lack the spiritual oomph Stuppin now gets, effortlessly, from painting the Sonoma coast.

Yes, this is a kind of regionalism. But it is not a defiant regionalism, a "regionalism" akin to a more-narrowed "nationalism." It is a regionalism of marvel, a regionalism of adoration and elective affinity. It is a regionalism sourced in the investigation of the exotic - Stuppin was born and raised in New York - that in the ecstatic intensity of the investigation has translated into identification with the observed. Stuppin works in and with the Sonoma coast as Asher Durand worked in and with the Hudson River Valley, as John Kensett worked in and with the Massachusetts coast, as Albert Bierstadt worked in and with the wide-open West, and as John Marin worked with New York City. Indeed, in spirit and in style, Stuppin's Sonoma recalls Marsden Hartley's Maine, although Stuppin is more gently factual, with little of Hartley's (or, for that matter, Maine's) cold turmoil.

Note, though, that Stuppin's first identification is with art itself, with the act of painting and the process of looking at paintings (and other artworks). There may be a factual (although not veristic) basis to his art, but it does not suppress the fulmination of the hand or the liberal intervention of the eye. A child of modernism, Stuppin lets the photographers make the pictures; he makes the paintings, and in doing so finds an ineffable facet to coastal Sonoma, amplifying its extraordinary qualities without losing its quotidian integrity. In this he slouches towards the codifications of subjectivity that we find practiced, even preached, by the northern European expressionists working a century ago in the eye of the modernist hurricane. Stuppin's work, in purpose and intensity, aspires to the transport - some of the transport, anyway - seen in the volatile, yet highly ordered, landscapes of Wassily Kandinsky and, especially, Alexei von Jawlensky, realized in the Munich exurb of Murnau. Stuppin, we can see, conjures the rills and ridges of the Sonoma coast with the same loaded brush as that with which Jawlensky caressed the Alpine foothills; and, while the color of the land allows Stuppin only intermittent access to the extravagant palette Jawlensky could bring to his much lusher surroundings, the attitude towards color is the same: let it rip, let it glow, let it spill its embarrassment of riches all over the retina. (Stuppin shares a Russian heritage with the two Blaue Reiter painters, and has attributed his love of color to, among other things, the splendors of the Orthodox rites that comprised an important part of his childhood.)

Where Stuppin finally diverges from Jawlensky and other early 20th-century landscape painters, Blaue Reiter and otherwise, is in his spiritual purpose. They strove to embrace the landscape, to be in the flow with it as if in flow with a lover. (Issues of domination, by the way, were secondary, or even beside the point, for these nature-worshipers, in whose number were included powerful women painters such as Gabriele Münter and Marianne von Werefkind.) Stuppin's goal is no less ambitious, but is at once more benign and more emphatically self-effacing: to flow with the landscape as if he were part of it. Whether or not this is a more modest goal, it is a less dramatic one. In its pictorial achievement, it achieves a picturesque quality, amplifying the attractive and simple aspects of the place. Stuppin has left to others the search for the sublime, which motivated the German painters and brought them finally into abstraction. But in not seeking the sublime, Jack Stuppin has found his own abstracted voice, a voice that does not speak of the landscape, or for that matter to it, but in it.

Peter Frank, Art Historian and Critic

Years ago, a friend of mine in Philadelphia, an artist, was telling me about her drive out west, through Wyoming and Montana and here. She enthused about the variety and especially the drama of the topography, all the ups and downs and ins and outs and darks and lights and colors and textures. She described it as "landscape sex." I suspected she was doing so in order to divert my attention and to keep our own interaction on a Platonic plane, but I had to admit she had a point. Landscape is sexy. And, as you can see, Jack Stuppin agrees, with no little passion.

Jack's show here is called "Sensual Landscapes." But that's the PG version. His regard for the landscape, especially the effulgent and abundant landscape that stretches between his home in Sebastopol and the Pacific Ocean, is downright libidinous. The way Jack paints, you want to run your hands all over his paintings - AND all over the actual hills and groves and waves and clouds he paints. And you fully expect the landscape, and the paintings, to caress you back. Fortunately, Jack is too much the gentleman to paint pornographic landscapes, and has developed a style that, like any good party outfit or date movie, still leaves something to the imagination. Jack's paintings look as if they've sprung from the imagination in the first place, but in fact they are largely reportorial. Without being literal, they tell it like it is. The Sonoma coast looks like this. Or perhaps it's more accurate to say, it feels like this. Which makes the show title "Sensual Landscapes" make sense. Except that the title doesn't indicate what a turn-on the landscape and Jack's response to it both are.

If you're a cinema buff you'd probably compare the paintings to those films that European directors write and shoot, movies that star their lovers or spouses, movies that capitalize on their makers' deeper sense of the objects of their gaze. So often, these films are not about the satisfaction of desire but the perpetuation of desire, the self-amplifying quality that looking at or thinking about your beloved causes. That same frisson builds up in these paintings, until you want to jump into them and become paint yourself. You want to disappear into Jack's pictures and never come back - and not even disappearing into the real landscape out there by Bodega will do. Jack goes out there all the time, embraces his landscape love, comes back to the studio, does larger, more polished versions of his encounters, and then goes back for more. And in that way he keeps US coming back for more. Landscape sex is the love that dare not speak its name - and, at the same time, is the love that can't keep quiet.

by Mark Van Proyen

Professor of Art History, San Francisco Art Institute

Contributing Editor, Art Week magazine

To look at any one of Jack Stuppin's landscapes is to see two obvious things: configurations formed out of colorful, glistening paint and the idealized pictures of a luxuriant natural world. From this description, one might go on to say that it is equally obvious that Stuppin's vibrant depictions are conveyed to the viewer's eye by the exaggerated chromatics of the paint that he uses, and that would also be true, or at least true enough. But that is where their real story begins rather than ends, because the essence of that story lies in what is found in the transitional space between paint and picture. Here, we gain a glimpse of the kinetic geology that is in a perpetual state of insistent slow-motion eruption, always operating at the heart of the paintings' deceptively benign appraisals of places lying far beyond the outer fringes of exurban encroachment.

In large oil paintings such as Laguna Trees (2005) or St. Helena from Pine Flat Road (2006) the compositions are predominated by baroque renditions of rather fantastic looking foliage. In these works, up thrusting tree limbs support perfervid clumps of twig and leaf, all leaning over clots of groundcover that bears a startling resemblance to the well-stocked produce section of an upscale supermarket. At cursory glance, the painterly treatment of these tangles of foliage might seem to err on the side of decorative repetition, but closer inspection reveals the abundant delights of elaborated theme and variation in those places where pattern might have initially seemed to hold sway. Like the interpenetrating lines of music that come together to form a four-part fugue, the brisk swirling brushstrokes from which Stuppin's verdant clots of pyrotechnic color are carved seem to carry their own unique voices with them, even as they also merge into a chromatic polyphony that in turn merges into the larger panoply of these paintings' compositions.

In 1995, Stuppin arranged for an extended visit to the Farallon Islands some twenty-five miles beyond the Golden Gate, probably making him the first artist to paint their stark juxtapositions of bare rock and angry sea since Albert Bierstadt visited them in the early-1870s. Plein air paintings from this and subsequent visits were first exhibited at the California Academy of Sciences in the fall of 1997, and in 2005, Stuppin began a series of large oil painting that re-worked the compositions of the earlier efforts. But in this reworking undertaken in the relative comfort of the studio, something else began to happen, as the elements of sky, ocean and rock began to take on a more animated quality, seeming as if they were antediluvian characters awakening from a long slumber. We see this clearly in the elongated pyramidal geology made up of inverted v-shaped brushstrokes in Window Rock (1st version, 1995; 2nd version, 2005), and we also see it in the progression of arcs describing the dome-shaped rock in the center of the composition of Main Top (1995/2005), looking so much like the furrowed eyebrows of a bald giant enticed out of the turbulence of a primal soup by the fluffy custard clouds situated just above his head.

Reviews

FromSoftwareToPleinAir, Plus Minimalism in Heaven

by Peter Plagens / Jan 29, 2016

Jack Stuppin, Tauba Auerbach and Ann Veronica Janssens in this week's Fine Art

Call it "The Case of the Not Really All That Naif, Faux-Naif Painter." The gallery's press materials say, "Though born in Yonkers, New York, in 1933 and educated at Columbia College in New York City, Jack Stuppin eventually heard the call of the Golden State, where he studied art at the San Francisco Art Institute. Jack Stuppin remained in Northern California and settled in Sonoma County. For several years, he was a member of the Plein Air Group; The Sonoma Four - William Paul Morehouse, Tony King, Bill Wheeler and Jack Stuppin."

What's not mentioned is that before Mr. Stuppin became a painter, he was an entrepreneur, founding a company that manufactured computer software, and he didn't move north of San Francisco until the 1980s.

What's also not mentioned is that Mr. Stuppin relies partially on the computer to make his work - first digitally scanning small paintings, and then making larger digital prints of them to form underpaintings for the final versions. Afterward. he applies thick, bright, opaque pigments, making borderline psychedelic pictures that look as if the paint were squeezed directly out of the tube.

Mr. Stuppin's method of starting his pictures may strike some as too rote for the art of painting, but the 27 works in his exhibitions are zingers. Some of them, of course, are zingier than others, particularly "Oak and Hills" (2008) and "Bodega Head" (2003). Mr. Stuppin's seascapes are best, and his clouds - looking as strangely solid as anything ever painted by the great Canadian "Group of Seven" artist Lawren Harris - are his forte. The gallery could ratchet back the lighting a bit; Jack Stuppin's landscapes have enough visual horsepower as it is.

Constructing the (New) Sublime?

Jack Stuppin at ACA Galleries, Manhattan, USA

13 JAN 2016 by DANIEL GAUSS

When English painter Thomas Cole came to the US in the early 18oos, he began painting landscapes from the Hudson River Valley, attempting to capture and convey what Edmund Burke had called the sublime. To Burke, the sublime was astonishment bordering on terror. "The mind is so entirely filled with its object that it cannot entertain any other, nor reason on that object which fills it." Burke also dealt with the beautiful, which was distinguished from the sublime by the capacity of the beautiful to engender a desire to possess what was being viewed.

One could argue that the environmental devastation since the time of the Hudson River School was due to a rejection of the sublime in favor of mathematical analysis and technological profiteering along with a perversion of the beautiful toward the possession of the exploitable. By revisiting the Hudson River School movement in his show "Homage to the Hudson River School", Stuppin, therefore, revisits these two concepts in light of the development of science and technology and the ravaging of the environment for profit. He also, perhaps, questions the extent to which anyone should have bought into either extreme of transcendence or technological exploitation in regard to the American natural environment.

Stuppin uses super-enriched colors for his paintings. Sometimes the colors correspond somewhat to the colors we would expect objects to be, other times they do not. He takes the basic colors of nature, enhances them With a type of luminescence, and sometimes shuffles the colors somewhat so that, for instance, you get blue trees. Charles Burchfield admonished American landscape painters not to paint what they saw, but to paint the hidden, real presence of nature and, consequently, one might guess that these brilliant colors could be thought to reflect the elan vital we seem to sense when we engage nature on its own terms, free of cognitive and emotional baggage.

However, it could be that Stuppin points at those aspects of nature that engendered the transcendentalist tradition and hints at what gives nature its capacity to arrest and overwhelm us and con us, frankly, into believing in an elan vital. We get an awareness of our acceptance of the ancient belief in transcendence and union with nature, which has still not been destroyed through science, but which modern science seems to have refuted. In the paintings this elan vital, therefore, is not necessarily to be believed but becomes the starting point for us to become more aware of the limits of our cognition and emotion when contemplating or experiencing nature without the aid of science.

Along with brilliant colors, Stuppin also seems to present what might be called a natural world of averages. For example, I noticed in one painting that he does not have realistically depicted small, medium and large waves or waves of many shapes and sizes vis-a-vis each other; he shuns realistic, individual depictions in favor of rolling rhythmic patterns - his waves, for instance, are basically waves you might get if you took the average size of waves in one area. We learned in the early 20th century that observation changes the thing observed and so we get objects represented by averages instead of individually depicted objects. They are stylized waves imitating and perhaps replicating each other, perhaps intimating the concept of infinity.

Perhaps Stuppin wants to say that when we artistically depict and interpret an experience of nature, without applying any incisive background knowledge of nature to it, with viewers just standing in the presence of the depiction of nature, we are being engaged, basically, by colors and forms, no more, no less. What do we really hope to get from the colors and forms of landscapes? How might it be possible for these colors and forms to even imply a mystical or emotionally moving concept? In the direct presence of nature, colors and forms combine with our previous experiences of the textures of nature - how stone, wood, water etc. feel - as well as sound and smell. But is this even enough to derive that something extra, that deeper knowledge or understanding that nature seems to promise us through our contemplation of it, but which may never be disclosed?

Therefore, Stuppin might be asking whether the transcendental 'union' promised through much landscape art from the past is possible. Is the mind separate from nature or is it such a part of nature that it allows a deep intuition of the essence of nature? Stuppin's work might be saying that what we experience when we engage nature is not nature but the emotions created when we desire to understand but have insufficient tools to do so - neither intuition nor science gets us to the Faustian place we wish to go.

Intuition from an experience in a state of nature leads to mysticism, ritual or mythology, while science leads to the physical destruction of the environment. Yet, this middle ground we want between intuition and science becomes the palpable inability to grasp what we believe is possible to grasp and it becomes a grand experience in itself. The great mystery of landscape painting illustrated through the work of Stuppin is that Burke was right - in the presence of nature we are often overcome by an intense but difficult to describe emotion which subsumes everything else we might feel. It is joyous and painful and goads us to further and deeper experiences while leading to a lingering and obscure longing. Just what we are getting when we give ourselves over to that process is brilliantly and seductively represented by these perfectly executed works by Jack Stuppin.

Exhibitions

- 2016: ACA Galleries Solo Show / January

- 2016: ACA Galleries, New York, NY, Homage to the Hudson River School, January 7–February 20

- 2011: Pepperwood Preserve, Santa Rosa, CA

- 2010: ACA Galleries, New York, NY, Songs of the Earth, March 27–April 24

- 2009: Sonoma Academy, Santa Rosa, CA / Sonoma Landscapes, April 9–May 25

- 2009: San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA / Songs of the Earth, January 8–April 15

- 2009: Meridian Gallery, San Francisco, CA / Songs of the Earth, January 15–February 28

- 2007: B. Sakata Garo, Sacramento, CA / Lay of the Land, March 6–March 31

- 2006: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. / Landscapes en Plein Air, May 5–May 30

- 2005: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC / Landmark Gallery, Bodega, CA / Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

- 2004: B. Sakata Garo, Sacramento, CA / Sensual Landscapes, February 3–February 28

- 2003: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA / Los Angeles Art Show, October 9–October 12

- 2003: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA / Pilot Hill Collection of Contemporary Art, December 20–February 23, 2003

- 2002: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA / En Plein Air, September 6–October 9

- 2002: Sonoma County Museum, Santa Rosa, CA / Where Land Meets Art, June 6–September 6

- 2001: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA / www.calpaintings.com

- 1999: Quicksilver Mine Company, Sebastopol, CA / Sonoma Landscapes, April 8–May 12

- 1998: Sebastopol Center for the Arts, Sebastopol, CA / Sonoma Landscapes, October 9–November 18

- 1998: Columbia University School of Fine Arts, New York, NY / The Raw Facts of Nature, April 2–April 24

- 1997: 333 Bush Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1996: Bradford Gallery, San Anselmo, CA

- 1995: Cultural Arts Council of Sonoma County, Santa Rosa, CA

- 1995: Ebert Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1995: The Paint Store Gallery, Freestone, CA

- 1995: Bradford Gallery, San Anselmo, CA

- 1995: University Club, San Francisco, CA

- 1986: University Club, San Francisco, CA

- 1973: Pantechnicon Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1972: University Club, San Francisco, CA

- 1969: University Club, San Francisco, CA

- 2011: ACA Galleries, New York, NY

- 2011: Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY, Paintbox Leaves: Autumnal Inspiration from Cole to Wyeth, September 25–January 16, 2012

- 2011: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA, Permanent Collection

- 2010: Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, NY / Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

- 2009: de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara, CA, Permanent Collection

- 2008: Astana, Kazakhstan / Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

- 2008: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC

- 2008: B. Sakata Garo, SELZ, Sacramento, CA

- 2007: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

- 2007: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC

- 2007: B. Sakata Garo, SELZ, Sacramento, CA

- 2006: San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

- 2006: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC

- 2005: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC

- 2005: Landmark Gallery, Bodega, CA

- 2005: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

- 2005: Landmark Gallery, Bodega, CA / Landscapes of the California North Coast, June 3–August 10

- 2004: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

- 2004: National Endowment of Arts, Washington, D.C.

- 2004: Gallery C, Hermosa Beach , CA

- 2004: San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA

- 2004: Pilot Hill Collection of Contemporary Art / December 20–February 23, 2004

- 2003: National Endowment of the Arts, Washington, DC

- 2003: Butler Institute of American Art, Youngston, Ohio

- 2003: Fine Arts Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christie, TX

- 2003: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

- 2003: Quicksilver Mine Company, Forestville, CA

- 2003: Landmark Gallery, Bodega, CA

- 2003: Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi, TX

- 2003: Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH / Pilot Hill Collection of Contemporary Art, June 22–August 17

- 2003: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA, Pilot Hill Collection of Contemporary Art / August 21–February 23, 2003

- 2002: Plaza Arts, Healdsburg, CA

- 2002: Herbert Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, En Plein Air, September 6–October 9

- 2001: Claggett-Rey Gallery, Vail, CO

- 2001: Landmark Gallery, Bodega, CA

- 2000: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, CA

- 2000: de Young Memorial, San Francisco, CA

- 2000: John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA

- 2000: Lew Allen Contemporary, Santa Fe, NM

- 2000: Art Documento 2000, International Center of Culture & Spiritualitya’ Fra’ Beneditto, Sillico, Italy

- 2000: Quicksilver Mine Company, Sebastopol, CA

- 2000: Cultural Arts Council of Sonoma County, Santa Rosa, CA

- 2000: John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA, California Landscape Exhibition, July 1–August 30

- 1999: Sonoma State University Art Gallery, Rohnert Park, CA

- 1998: Gallery Szent-Gyorgi, Falmouth, MA

- 1997: Sonoma State University Art Gallery, Rohnert Park, CA

- 1997: California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA

- 1997: Bradford Gallery, San Anselmo, CA

- 1996: California Museum of Art, Santa Rosa, CA

- 1996: Bradford Gallery, San Anselmo, CA

- 1996: Frankie Waters Gallery, Bodega Bay, CA

- 1996: Sixth Fence Show, Sebastopol, CA

- 1996: Occidental Center for the Arts, Occidental, CA

- 1996: Donkey Barn Show, Occidental, CA

- 1996: Ebery Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1996: Millennium Arts, Sebastopol, CA

- 1995: Falkirk Cultural Center, San Rafael, CA

- 1995: George Krevsky Fine Art, San Francisco, CA

- 1995: Bradford Gallery, San Anselmo, CA

- 1995: I. Wolk Gallery, St. Helena, CA

- 1995: Fifth Fence Show, Sebastopol, CA

- 1995: King-Heller Gallery, Bodega, CA

- 1994: Fourth Fence Show, Sebastopol, CA

- 1993: Century Association, New York, NY

- 1993: Patricia Stewart Gallery, Napa, CA

- 1993: Third Fence Show, Sebastopol, CA

- 1993: St. Francis Memorial Hospital, San Francisco, CA

- 1992: John Berggruen Gallery / San Francisco, CA

- 1992: Patricia Stewart Gallery, Napa, CA

- 1991: Juniper Gallery/Napa Art Center, Napa, CA

- 1991: Napa Valley Museum, Napa, CA

- 1991: Dominican College, San Rafael, CA

- 1991: J. Noblett Gallery, Boyes Hot Springs, CA

- 1990: First Fence Show, Sebastopol CA

- 1989: John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1989: DIFFA Showcase, San Francisco, CA

- 1989: University Club, San Francisco, CA

- 1988: Braunstein/Quay Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1985: Vorpal Gallery, San Francisco, CA

- 1969: San Francisco Art Festival, San Francisco, CA

- 1968: San Francisco Art Festival, San Francisco, CA

- 1967: San Francisco Art Festival, San Francisco, CA

.jpg)

.jpg)